BIFF, CHIP & BIGOTRY

Why challenging bias is our imperative

It’s almost never in the big things.

You don’t see “No dogs, black or Irish” on restaurant signs anymore, the skinheads that used to go out ‘P*ki-bashing’ are of retirement age now and National Front “white is right” placards probably wouldn’t fly today. No, instead it has morphed. Structural racism and her deformed sibling- Islamophobia- has largely become insidious to the point of being innocuous. It’s in the discursive air that we breathe, it’s in the climate around us where we passively absorb ideas about ourselves that range from mildly inaccurate to wildly malicious. More concerning, for generations of children, their perceptions of themselves and others are being formed in a climate that requires razor-sharp focus to weed out the invisible and inherent bias in the media we absorb and systems we partake in.

We have already seen what happens at the ugly intersection of anti-Muslim bias and the modern education system. The Trojan Horse affair hinged on a letter apparently exposing a fanatical Islamist plot to take over schools, wrecking careers, institutions, and entire lives in the process. The government’s Prevent policy encourages civil servants to report and monitor the behaviour of free citizens, apparently conflating mundane aspects of religious practice with ‘signs of radicalisation’.

When Kiran Mirza’s son came home with a copy of “The Blue Eye” in the hugely popular Biff, Chip and Kipper series, it was the last place one would expect to find anything near contentious.

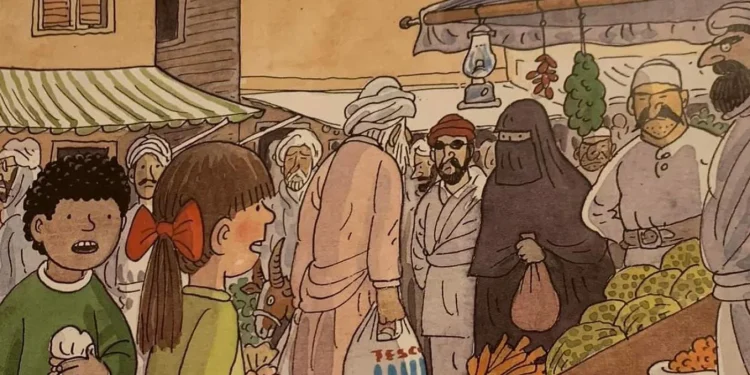

So, what did she see? An illustrated double page spread of a market section (or ‘souq’ for the cultured among us) presumably set in the Middle East/Arabia/some exotic brown destination. Those who have come out for their spices and incense are robed in turbans and niqabs (face coverings) and- for reasons unbeknownst- seem to be collectively scowling at a defenceless Biff and Wilf who have been magically transported to a ‘scary town’.

One would assume in the hustle of a busy marketplace, there would be chit chat, bartering, and wares being curiously inspected. Instead, all the brown people in religious garb have eyebrows furrowed and faces glaring. The line: “the people do not seem very friendly” speaks to every racist trope that visible Muslims are accustomed to seeing in public discourse. You can’t be visibly Muslim and just going about your day-to-day tasks- with the regular range of emotions of any other human being- dressed any other way- experiences. You definitely cannot be a bearded Muslim male and smiling and what’s that? A woman in hijab simply living her life, and not cowering in fear of her oppressive (ergo: NOT smiling) husband?

Mirza brought this image to the attention of an online community group- Muslim Mamas- and users created a successful Twitter storm to raise awareness around the book content in circulation. As a result, The Blue Eye has been withdrawn from sale, all remaining copies have been pulped by the publisher Oxford University press. All major news outlets have picked up on the story and online discussions have reignited around perverse depictions of minority group, normalised anti-Muslim prejudice, and the social responsibility that those involved in educating children have.

“Oh, it’s only a picture! What’s the big deal?”

The minimising of this kind of every day bigotry is what contributes to an overall climate of normalising Othering. It creates internalised Islamophobia within our children (and indeed ourselves as parents) and may cause the stutter in your child as they have their name mispronounced or are asked about some dietary requirement of theirs. It may have them actually believing that their ‘own’ are the grimacing uncles in beards and creepy women in niqab: who can help you once you have learnt not to be comfortable in your own Othered skin? As Malcolm X once so powerfully asked: “Who taught you to hate yourself?”

The dehumanisation of the Other rests on not only emphasising how distant the boundary between “them” and “us” is in terms of outer clothing, but how alien, negative and repulsive their belief, character and state of being is.

Worryingly, publishers pulled the book after calling it ‘no longer appropriate’, which begs the question: when was it ever appropriate? Originally published in 2001, two decades doesn’t take us back into a world where there was no awareness around Orientalist or racist depictions of minority groups, subliminal messaging or the harms of Othering. Words like ‘diversity’, ‘inclusion’, and ‘representation’ are not new in our lexicon. The range of people involved in a publication like “The Blue Eye” (editor, illustrator, designer, writer, publisher) indicate that the depiction of Muslims here wasn’t a slip or faux pas, but something so ‘passable’ as to make it to print without eyebrows raised. Or that for all the languages and departments created, systemic racism steam rolls ahead despite performative lip-service to the contrary.

We owe it to ourselves, our children and our community to continue raising our voices when we come across problematic content, in whichever field. We must educate ourselves on effective ways to dissent and object and support the advocacy groups who are already doing essential work to this end. We must keep our ear to the ground and understand that only through collective and consistent pressure, change truly occurs.

Every issue matters. Every raising of concerns is important. Never belittle the importance of resisting structural racism- whether it is a line in a book or an entire employee manual. Though it seems like one is swimming against the tide, acts of resistance are the only raft that will keep us and our communities afloat. As believers, we don’t measure our efforts by material results either. Though in this case, a satisfactory outcome was reached, it may not always be. That does not mean we simper down however. Actions are weighted by their intention and the divine recompense for our actions are never lost: on the contrary they are stored for a reward on a Day we will need it most. Until then, we remain engaged, active and aware. This is a fight for all of us.