WHY WE MUST QUESTION, NOT ‘SHATTER’ STEREOTYPES

So why did I want to put myself through that? Something inside me was shifting. My religion was on television and in the papers daily, yet I knew little to nothing of it. I decided it was time to dive in and learn about it from scholarly sources. That meant reading a ton of books, seeking out experienced teachers and asking endless questions. Exploring Islam in a knowledge-based way meant wearing hijab was simply to harmonise my outer appearance with the inner contentment I found through a deeper understanding of my religion. It felt good and the pieces were falling into place. Except, sometimes puzzle pieces have jagged edges. To go from seamlessly blending into the mainstream (or at least ‘passing’ for the ‘right kind’ of exotic) to being so dramatically othered literally overnight carried many sharp and unexpected lessons.

The power carried in a single cloth suddenly made it a potent symbol for whatever people chose to read into it – whether one loved, loathed or feared it. One of my niggling concerns was that in wearing the hijab, people would stop interacting with me as an individual, but with their assumptions of what identifiably Muslim women are. That hunch turned out to be true, time and again. When a woman goes from looking like ‘one of us’ to being othered through hijab, then actions that are routine parts of a full and active life are suddenly framed as ‘shattering stereotypes’ and ‘breaking the mould’. Representing our post-graduate class to university management, or mentoring undergraduates in Psycholinguistics, were useful but unremarkable things that I did before I started wearing hijab. A simple head covering suddenly turned these same acts into ‘challenging norms’- though it was still same old unexceptional me behind it.

Within the first week of wearing hijab, I visited the GP to make an appointment. A receptionist took a quick glance at me before flatly asking, ‘Will you need a translator?’ She obviously didn’t recognise me because she was the same lady I’d had an enthusiastic conversation with the week before, where we discussed how to successfully germinate avocados indoors. But that day there was to be no chit-chat about botany. Today, a simple cloth called into question my ability to even speak. I felt scrubbed out, dehumanised, and had a sinking feeling this would become a reality I’d have to get used to. During some pre-class small talk, one adult English language learner asked me, ‘I wonder when the teacher is arriving?’, to which I stood up, turned on the overhead projector and said, ‘I’m already here!’ with a smile. The moment of wide-eyed silence as it sunk in that it was me who would be teaching the joys of the past participle hung heavy in the air for those few seconds. I have to admit, I’ve had to suppress internal groans when I’ve been enthusiastically assured, ‘you really aren’t a stereotypical Muslim woman’ or ‘I didn’t expect you to be like this, it’s so refreshing’. Such comments usually come after I have spoken clearly and confidently in a public space, or have had a nuanced and reflective conversation with colleagues and friends.

This is because the stereotypes about visibly Muslim women are effectively tightly constructed, reductive and often heavily policed boxes, which attempt to present over half a billion women as banal monoliths. Any deviation from the usual clichés around Muslim women (uneducated, oppressed, lacking agency) are met with patronising applause and eager, approving head-nodding. I’d be lying if I didn’t say I make an above-average effort when interacting with people in public. I make small talk with the supermarket cashier, really help people who stop me for directions and make sure I have a smile and open demeanour as much as I can. Why do I have this subconscious need to ‘perform’ niceness while hearing hijab? Because I know I am visibly representing a group that is often treated with disdain, paranoia and a shed load of presumptions. I should not have to play the ‘approachable, friendly Muslim woman’ in public, but for as long as these stereotypes abound, I know I will succumb to the pressure to.

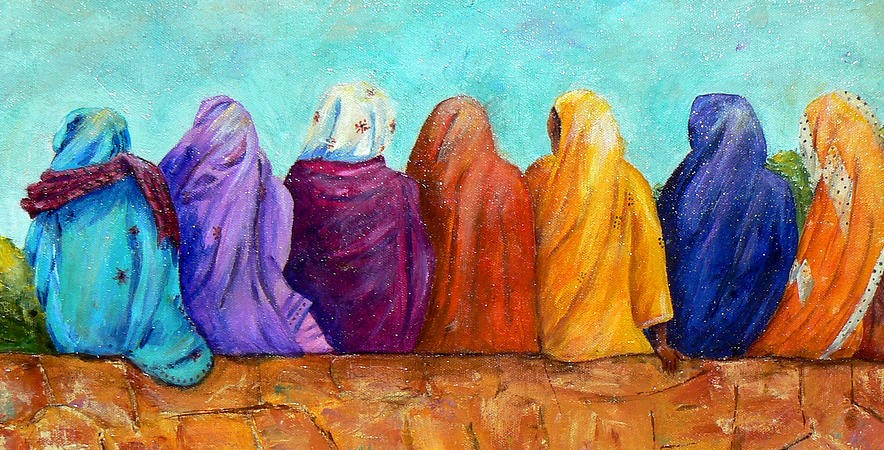

Now when I’m told I’m ‘breaking stereotypes’ by those who often mean well in their enthusiasm, I ask them why they are so surprised – what are their stereotypes and where did they come from? The call here is as simple as it is so borderline obvious, it should hardly need an article… yet here we are. When it comes to Muslim women – or any marginalised groups – let us begin by truly humanising one another. That is to see others in the same complicated, varied, conflicted and evolving way we see ourselves. Resist the repetitive assumptions which routinely permeate the very air we use to put others into lazy and dangerous boxes. Under the hijab on a Muslim woman’s head is a fully functioning human being, just like you.

This article originally appeared here.