I REFUSE TO CONDEMN: STORIES FROM US AND FOR US

It was the day after September 11th 2001 – the very first time I was asked to condemn.

The common room in my sixth form college was heatedly debating what had just happened the day before. The atmosphere was so charged you could almost feel the adrenaline bounce off all of us clueless teenagers trying to understand the gravity of what had unfolded. Going into college that morning, I remember the front page of the Daily Mirror reading “The World at War”, with a lone image of the second plane hitting the towers.

“They should nuke the Middle East in response.”

“Bin Laden works for Mossad.”

“Nostradamus predicted this.”

This was just a selection of the piercing political analysis discussed that day. Then came:

Queue me being asked,

Then came trying to explain where Afghanistan even was:

“No, it’s in South Central Asia, a landlocked country bordered by -”

“Never heard of it.”

“Okay… have you seen Rambo? Rambo III… He went there.”

“Oh yeah, I’ve seen that. So you’re related to Sylvester Stallone?”

On one level, it was all just idiotic banter between teenagers who then went back to their polyphonic ringtones straight after. As the next few years wore on, however, the presumptions about my position on 9/11 remained. The tone of questioning became more sophisticated and, at times, insidious. Simply existing as a Muslim (observant or otherwise) became a political position.

Front covers of newspapers would run with stories like “Muslim cabbie refuses guide dog” and “Muslim pharmacist refuses to dispense morning after pill”. The barely concealed Othering and incitement of moral panic was full steam ahead; no conversations ever remained neutral after that point.

Most political talk began with the litmus test of “What do you think of 9/11?” This was a veiled shorthand for “Are you happy nearly 3000 American civilians were killed?” Because being cool with mass murder was framed as a likely and plausible position any identifiable Muslim would hold. On the flip side, I will never forget a visiting scholar who taught me as an undergraduate for over a year and who said goodbye to me by squeezing my shoulder and saying, “I think America had it coming too.” Too? Wait, what?!

I wonder what is more offensive: people needing you to confirm you’re not okay with killing, or privileged liberals reassuring you they “don’t mind” that you are indifferent to civilian death? All of those experiences no doubt became one of the lenses through which my reading eye approached the collection of essays I Refuse to Condemn, edited by Dr Asim Qureshi.

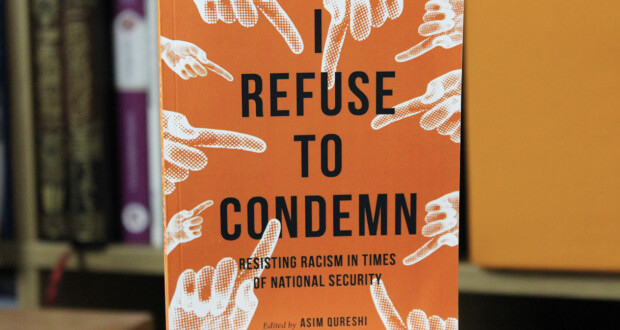

The Title

The startlingly bold orange cover of the book has an Andy Warhol pop art vibe to it, with wagging fingers pointing to the bold uppercase lettering “I REFUSE TO CONDEMN”. On first glance, such a title can be seen as borderline petulant. It seems a petty stance to take so strongly, because, after all, what is the big deal? Surely when people ask you to condemn violence, they only want you to make your position clear. Yet this book deals with the iceberg under the surface of such a question. Why would your position be unclear in the first place? Who made it unclear? Why? Is saying anything going to provide your questioner desperately sought clarity and relief? Who is questioning? What are the true dynamics at play behind the seemingly innocuous question of whether a Muslim condemns terrorism after any given incident?

The People Behind the Stories

One can call the chapters in the book essays, contributions, or analyses, but I prefer to call them stories. The book brings together the lived experiences of 17 scholars, activists, community organisers, and humans touched by the invisible power behind this demand for condemnation.

The stories themselves are short and sharp hits inside lived realities that provide points to pivot from and plenty of nuance and depth through such paucity of words. The strength of the stories is not borne from fancy language or juicy exposés – they come from raw authenticity. One cannot help being drawn to those who can speak from a place of truth and integrity, crystallising what many within the Muslim community have felt but have never articulated. The vulnerability it takes to recount experiences that are personal, political, and public all at the same time is rare to find. In this way, the book seems to be aimed at the community its contributors are borne from, as well as others interested in hearing genuine and unfiltered personal accounts. There doesn’t seem to be a similar offering within the existing literature, so to this end, each of the contributors succeed in pioneering a long overdue narrative of the many faces of resistance.

Introduction from the Editor

The book opens with an introduction by its editor, Dr Asim Qureshi, hooking from a personal experience being interviewed by veteran Channel 4 journalist and all-round liberal darling Jon Snow. The confusion, betrayal, and sinking acceptance that the insistence to ‘condemn’ could easily and obliviously come from Snow, even him, triggered an unnerving physiological reaction within Dr Qureshi.

There were so many things that struck out for me during this introduction, the word ‘Power’ being given an uppercase ‘P’, for example. We all know power. We feel it, and indeed, it feels us too. We have an overt and subliminal sense of it at play. In this way, it feels almost omniscient, foreboding, and crouched in the inflection of a certain tone, or the curve of a particular kind of smirk. It often hides in plain sight too. But vocalising it, giving it form, and bringing it to attention often has one sounding like a ranting lunatic. Even that, of course, is another manifestation of Power. It is gate-keeping, propriety, the boundaries of discourse, and the acceptable terms on which we must show up.

The introduction then goes on to weave the relevance of each of the contributors together. Lines are always blurred between the different topics they cover under this umbrella of ‘condemnation’ and the climate it is borne from.

The Stories

Each individual essay contains its own unique gems and nuances, but one of the benefits of such a patchwork of voices is that clear themes emerge that speak to a unifying experience.

The Personal Cost: Anger, Cowardice, Fear

With so much happening on a policy, state, and media level, it is easy to forget the very humanness of the people interacting with invisible state violence. Dr Qureshi touches on this in the introduction, where he speaks candidly about the involuntary signs of trauma that his body experiences, even as he can simultaneously understand and intellectualise what is going on.

There is a spectrum of emotions that speak to the human impact. This could come in the form of the sheer frustration and futility of Shenaz Bunglawala being told that the protocol of delivering unconditional condemnation should be the “first rule of communication” for Muslim organisations speaking publicly about terrorism. Fatima Rajina speaks of the personal impact of her identity and roots being decimated and annihilated as they did not meet the standards of Whiteness she had come to accept as the norm. Tarek Younis speaks in a deeply vulnerable way how the yearning to be seen by others can often mean not honouring your highest principle. His essay toys with the themes of cowardice and bravery, and hooks off a deeply disconcerting interaction with a racist teacher at a formative time, the consequences of which are still being unpacked.

Azeezat Johnson provides an insight into the profoundly personal toll it takes as a Black Muslim female in academia forced to walk the ground of White supremacy but work within a framework of White innocence. To be able to truly confront the hypocrisy of White innocence is not so much an academic excursion as an exercise to call on her courage and truly trust herself. This echoes Younis speaking about him recognising and understanding his own cowardice and the debilitating fear that has held us all back at some point.

Sadia Habib speaks of forever being the racialised ‘go-to’ Muslim within academia, constantly asked questions about Islam as if Islam ‘speaks’ through her like a ventriloquist holding a puppet. This comes from a place of ignorance, but that ignorance is not excusable; it can even be threatening. Such ignorance is deliberate, negligent, and a privilege that a marginalised Muslim community is forced to perform to.

Lowkey (Kareem Dennis) talks about the range of internal emotions, from disdain to ‘playing the game’, during a stop and search with an officer trying to ingratiate himself to him by posing as a bit-too-keen comrade. Fahad Ansari speaks of his mother’s natural apprehension of his politically challenging the Government, as he defends clients that invite public revulsion. Ansari continues from principle while trying to allay his mother’s deepest concerns about the consequences of his choices.

Dr Yassir Morsi speaks of the blow that his own spiritual journey is forced to take in a climate that criminalises and Otherises one’s very existence. He is “tired, personally distracted and disorientated”, looking at everything with less intrigue and joy than he used to. Nadya Ali speaks of her struggle to process the grief and rage after the Christchurch mosque shootings, knowing all the while that the right-wing ideas that facilitated it were being legitimised in academia.

Being an Outsider from Within

It is a common experience for many Muslims to simultaneously occupy a role of being part of a community yet forever being seen as fundamentally Other to it.

Shereen Fernandez speaks painfully of the experience of appearing as a visible Muslimah while interrogating Prevent within academia. Fernandez negotiates bureaucracy as an academic with full awareness that her very body could be seen as a ‘risk factor’, according to Prevent training criteria. This echoes the experience of Saffa Mir when she co-founded the ‘Preventing Prevent at Manchester’ campaign, actively trying to resist a piece of legislation, while at the same time being subjected to it.

Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan writes how, within the frame of ‘poet’ and ‘spoken word artist’, she is presented a particular way, but her status as a visible Muslim woman inevitably renders her an outsider carrying narratives that often challenge the institutions that invite and wish to platform her.

The Gaze of Power

Right from the introduction, with Dr Qureshi’s upper-casing of the word ‘Power’, this theme ran through all the essays of the book. Power works by confining individuals into pre-allocated roles and binaries, penalising challenges and dissent to them. Tarek Younis writes of making peace with rejecting the gaze of Power despite its lucrative offerings for those who partake in the system. Refusing to condemn necessarily entails finding comfort in existing outside of the gaze of Power.

Dr Yassir Morsi writes of the consequence of being constructed in someone else’s gaze. Dr Morsi uses the metaphor of a body growing into a shadow and how one is grown or projected into another version of oneself. The stereotypical Othering of the Muslim during the War on Terror is a mechanism of Power. Manzoor-Khan speaks of dodging the cages set up by those in Power and this being the heart of resistance. Hoda Katebi was told “you don’t sound like an American” for espousing views that rattled the narratives of Power on live TV. Nadya Ali appeals for our Ummah’s children to understand how Power looks upon them and to resist this gaze in the fight for intergenerational justice.

Power also forces people to position themselves within binaries that have already been constructed. One is effectively given the choice to ‘play within the parameters’ outlined or risk irrelevance, alienation, and being cast out as impossibly radical and unreachable. Aamer Rahman transcends this by openly and unapologetically performing his comedy for his community, understanding that a natural consequence of this is that he will likely never make ‘the mainstream’. Rahman writes of how he refuses to compromise on his integrity for mainstream acceptance, just as all the authors understand the personal cost of not desiring acceptance of the gaze of Power upon them.

A Final Thought

Of all the contributions, Dr Yassir Morsi’s The (Im)possible Muslim had the deepest impact on me. It was in equal measures beautiful as it was haunting. Drawing on the metaphors of shadows, trees, branches, webs, and knots, only the vast and shape-shifting nature of metaphor can hold the weight of his journey – a route many of us have also taken.

This book is important on a personal, political, macro, micro, state, and street level. Reading each author’s experience almost felt like a huge glass vase had smashed, each contribution lying in the shards left on the floor. They all have their own form and story, but ultimately, they are borne from the same vessel of the invisible power of state violence. This collection fills a vacuum many of us have long sought answers for.

There were times in the book where I felt a type of nausea that was germinating from roots long dormant; vicarious trauma, if you will. Each of us has lived through this, and there is power in bringing together strong, bold, and brave voices. Our lives fast become stale and stagnant when not involved in a righteous struggle.

These are stories of bravery, courage, challenging norms, taking a risk, and being willing to lose significantly. But most of all, these are stories from us, for us, and for the future of us.

This book review originally appeared here.